How to Reduce Phone Use Without Going Cold Turkey

If your phone use has started to feel more automatic than you want, you are not alone.

Many people are looking for relief, steadier focus, better sleep, and a way to feel more present without fighting themselves all day.

If you found this page while searching how to beat phone addiction or how to fight phone addiction, this article is meant to meet you where you are.

How to use this article

This article is designed as a general guide to help reduce phone use. It is not meant to be read as a checklist or completed all at once.

It moves through a few simple phases that build on each other, so you can take what feels useful and leave the rest.

Awareness and pausing

Mapping phone use and replacing needs

Adding gentle barriers

Zooming out to stress and overwhelm

You do not need to follow these steps perfectly or in order.

They are here to help you move at a pace that feels manageable and supportive.

I work with many people navigating technology-related habits and overwhelm. If you’d like support making changes that actually stick, you’re welcome to learn more about scheduling here.

1. A Pause Before You Try to Change Anything

Before you try to reduce phone use, it helps to slow down and simply observe.

Awareness comes first. It turns automatic behavior into something you can see, rather than something that just happens to you.

Noticing a pattern is already a form of change, even if nothing else shifts yet.

The moment you notice, autopilot has been interrupted.

When you observe your phone use with curiosity, you begin to see:

What situations tend to trigger it

What you are feeling right before you reach for your phone

What the phone gives you in that moment

What it might cost you later

Nothing needs to change yet. Think of this phase as collecting clues, not making commitments.

Take a breath, then move on when you are ready.

2. Creating a phone habit map

Before trying to change anything, it can help to get a clearer picture of how your phone use actually shows up.

You only need to answer once, and you can keep it simple.

When do I usually reach for my phone?

Name a time or situation, such as after work on the couch or lying in bed.What do I feel right before I reach for it?

Common answers include stress, boredom, loneliness, fatigue, restlessness, or overwhelm.What does the phone give me right then?

Relief, stimulation, connection, escape, reassurance, or numbness.What does it cost later?

Sleep, focus, time, mood, presence, or confidence.

This map helps you see what your phone use has been doing for you so you can meet the same need in a different way.

Small swaps work better than bans

Instead of trying to stop scrolling outright, add a pause and offer your nervous system another option.

A helpful swap does not have to be impressive. Our goal is to replace the need, not just the behavior.

Look through this list or come up with a healthy habit of your own.

If the phone was giving relief, a warm drink or one minute of slow breathing may be enough.

If it was giving stimulation, music, brief movement, or a tiny task can help.

If it was giving grounding, sensory input like cold water or texture can help.

If it was giving focus, writing the next smallest step and starting for two minutes is often enough.

Simply having one replacement for your needs is a good start.

You are choosing the next 30 to 120 seconds, not a new lifestyle.

Simple Summary:

Notice the pull

This is the moment you feel the urge to check your phone or realize you are already reaching for it. Even noticing after the fact counts. Awareness is the first interruption.

Pause briefly

The pause does not need to be long. One breath, setting the phone down for a few seconds, or naming what you are feeling is enough to create choice.

Redirect the need

A helpful swap replaces what the phone was giving you, not just the behavior itself. It does not need to be impressive or productive.

The goal is not to remove your phone.

The goal is to add a pause and offer your nervous system another option.

A Helpful Reframe

Most people do not need more willpower.

They need a plan that fits how habits actually work.

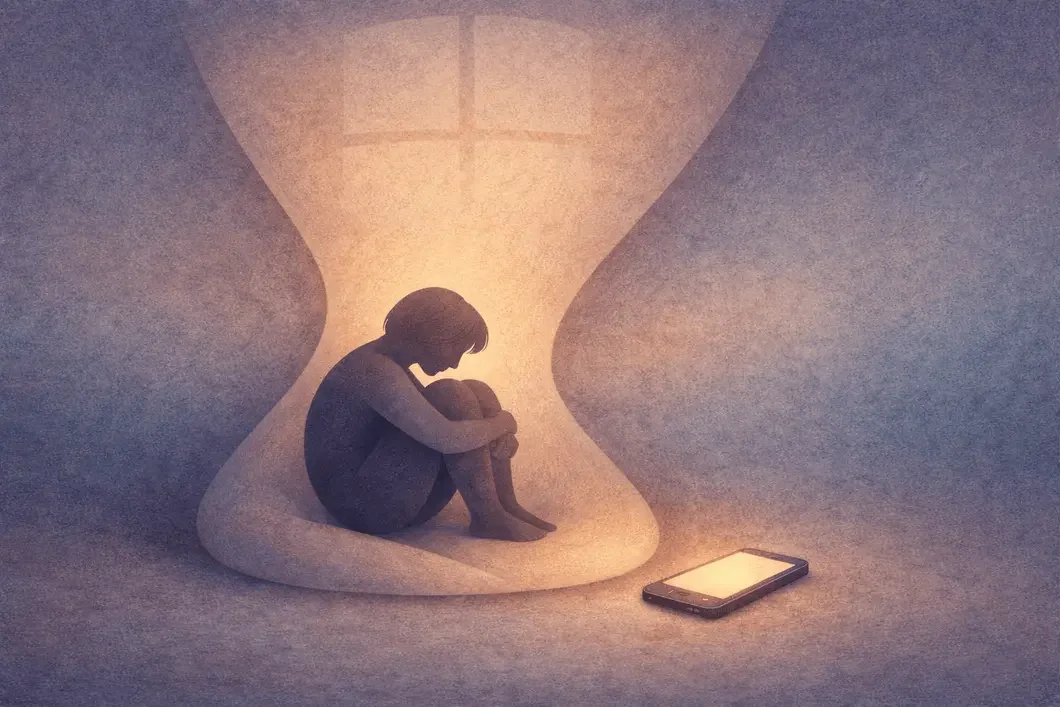

Phone overuse often makes sense in the moment. It offers quick relief, stimulation, connection, or predictability when something feels uncomfortable or overwhelming.

When your only strategy is “try harder,” it may work on good days and fall apart on hard ones.

That is not a personal flaw. It is a design issue.

Phones are built to be easy to reach for, especially when you are tired, stressed, or emotionally activated. In those moments, effort and reflection are already limited. This pattern is part of broader technology overuse dynamics that many people are navigating today.

The goal here is not to shame the habit or force control.

It is to reduce autopilot moments and adjust the conditions around the habit so more choice becomes possible.

Change tends to stick when it works with your nervous system, not against it.

3. Barriers - When Stress or Fatigue Make Phone Use Harder to Regulate

Late-night scrolling is a common example, but the same pattern shows up any time you are stressed, tired, or depleted.

When energy is low or stress is high, your nervous system looks for:

• Relief

• Predictability

• Minimal effort

Your phone fits all of those needs very efficiently, which is why patterns of phone and screen overuse often show up most strongly during stress or fatigue.

This is why automatic scrolling often increases:

• At the end of the day

• During emotionally heavy moments

• When you are sick or run down

In these states, relying on willpower alone is rarely effective.

Why Barriers Help in These Moments

Barriers are not punishments.

They are supports.

When you are regulated, you may not need them.

When you are stressed or tired, they quietly step in to slow things down.

A small barrier creates just enough friction to interrupt autopilot and allow choice to return.

Importantly, barriers work best when they are paired with an alternative, not when they remove access entirely.

Examples include:

Moving the phone out of reach during high-risk times, not only at night.

Keeping a notebook, book, or grounding object nearby so something else is available when the urge hits.

Setting time-based limits for high-stimulation apps during periods of fatigue or stress, while allowing lower-stimulation use if needed.

Designating certain places as phone parking spots during meals, work blocks, or rest periods.

These changes work because they respect how habits actually operate under stress.

So a small step that you can take is setting a simple barrier around the time when you are most vulnerable. This will give you the ability to pause and make better choices in those tough moments.

You may work around the barrier, that is ok. This just tells us that either the barrier needs to be changed, or that you have a strong need that your brain still is using your phone for.

4. Why Overwhelm Makes Phone Use Harder to Change

It becomes much harder to use your phone in ways that line up with your values when you are overwhelmed. For many people, anxiety can make screen use feel more urgent and harder to regulate.

This is not a motivation problem. It is a nervous system problem.

When stress is low to moderate, most people can pause, reflect, and choose more intentionally. When stress is high, the brain shifts into survival mode, prioritizing quick relief over thoughtful choice.

In that state, the system prioritizes:

• Speed over reflection

• Relief over long-term goals

• Familiar habits over new choices

This is often described through ideas like the window of tolerance, ACT, or polyvagal theory.

Different frameworks use different language, but they point to the same core truth.

When you are outside your window of tolerance, or feeling flooded, shut down, or overstimulated, values-based choices become harder to access.

Your phone is especially appealing in these moments because it offers:

• Predictable stimulation

• Immediate distraction

• A sense of control

This means that struggling with phone use is often a sign of too much stress, not too little effort.

Why This Matters for Reducing Phone Use

Reducing phone use becomes much easier when you are more regulated overall.

This does not require eliminating stress.

It means building small buffers that keep you closer to your window of tolerance.

Examples of buffers include:

• Adequate rest and sleep support

• Short moments of physical movement

• Regular meals and hydration

• Brief grounding practices during the day

These supports may seem unrelated to phone habits, but they directly affect how much choice you have available.

When your system is less overwhelmed:

• Urges feel less urgent

• Pauses come more naturally

• Slips feel less catastrophic

Observation is easier when you are not flooded.

Pauses last longer when stress is lower.

Swaps feel more appealing when your body is not desperate for relief.

If phone use keeps feeling out of control despite reasonable efforts, that is often a sign to work on your general lifestyle and stress instead.

This is why the goal is not perfect phone control.

The goal is more capacity.

What Success Actually Looks Like

Many people quietly measure success as stopping scrolling completely.

That standard is often unrealistic and unnecessary.

More helpful signs of progress often look like noticing sooner, scrolling for less time, choosing a different option once in a while, or recovering more quickly after slipping.

Success is less autopilot, not zero phone use.

If your phone still plays a role in your life but feels less controlling, that counts.

If You Only Try One Thing

If everything feels like too much, try this.

Identify one pattern where phone use feels most automatic.

Add one small pause.

Offer yourself one alternative that meets the same need.

That is enough to start.

You are not trying to redesign your life.

You are practicing one moment of choice at a time.

If you are wondering about mental health effects

Many people arrive here after searching how do phones affect mental health or how can cell phones affect your mental health.

Impact depends on the person, the pattern, and what phone use is replacing.

For some, phones support connection and organization. For others, they increase stress, comparison, fragmented attention, or sleep disruption.

If you are exploring signs of screen addiction or wondering whether your relationship with your phone has changed over time, a non-diagnostic look at common patterns may help.

How therapy can support change

Self-guided changes work best when stress levels are manageable and basic needs are supported.

But if you are still having difficulty it might mean there is more going on underneath the habit.

Some people search for phone addiction therapy, screen addiction treatment, cell phone addiction therapy, or mobile phone addiction treatment because they want structured, non-judgmental support.

Therapy can help you understand what your phone use has been doing for you and build a plan that fits your real life.

In counseling, we can clarify the needs under the habit, create boundaries that feel supportive rather than rigid, and practice regulation skills that make consistency more possible.

“If you would like support, therapy can offer a structured, non-judgmental space to work through this. You’re welcome to explore scheduling here.

FAQ

Do I have to quit my phone to change this?

No. Many people do better with small shifts than with bans. The goal is less autopilot and more choice.

What if I need my phone for work or family?

Then the goal is not less phone overall. The goal is fewer unplanned loops while keeping necessary use intact.

What if I try these and still feel stuck?

That often means the habit is tied to stress, anxiety, attention challenges, loneliness, burnout, or sleep patterns that need more support.

About the author

Joseph Brooks, MA, RMHCI, is a Registered Mental Health Counselor Intern at Brooks Counseling & Wellness in Florida. He works with adults and teens navigating technology overuse, attention difficulties, anxiety, and overwhelm in a digital world.

This article is written from a counseling and digital wellness perspective and is intended for education and reflection, not diagnosis.

Learn more about Joseph and his approach here.